Bude Invasive Species Bench

To celebrate the beginning of Invasive Species Week, this special bench was installed on Monday 24th May near the Tourist Information Centre and car park at Bude Canal, Cornwall. This bench can now be enjoyed by everyone and also helps to raise awareness of Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS), providing straightforward advice on how all canal users can tackle INNS.

As well as this, interested parties also attended a free workshop on Wednesday 26th May to review the problem of INNS at Bude Canal and to discuss management options.

CINNG is delighted to work in partnership with South West Water and local volunteers to raise awareness and take action on INNS. As CINNG Chair, Peter McGregor explained:

“CINNG facilitates working in partnership, which is the key to effective action on INNS. A particularly powerful partnership combination involves volunteers who are on site, informed and engaged, working with utility companies and national bodies.”

A massive thank you to Greenspace Designs Ltd for designing the beautiful artwork on the bench.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Southwest Invasive Speices Forum

One of the main highlights of Invasive Species Week was the Southwest Invasive Species Forum. This was one of many events raising awareness of invasive species across the UK and Southwest. During this meeting, CINNG got to chat to many people/organisations about what’s going on across the region to combat the impacts of invasive non-native species.

It was great to hear from everyone involved, here at CINNG we had a great day. A huge thank you to South West Lakes Trust and South West Water for hosting the event via Teams.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Signal Crayfish

Signal crayfish, which is a lobster-like freshwater species. It was introduced into the UK by the British Government in the 1970s, to be farmed for food, but quickly escaped and spread rapidly through the UK.

Since escaping it has driven the white-clawed crayfish towards extinction through competition and transmission of crayfish plague, which doesn’t harm signal crayfish but is fatal to white-clawed crayfish. It also burrows into riverbanks leading to erosion and increasing flood risk.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Montbretia

Montbretia (Crocosmia pottsii x aurea = C. x crocosmiiflora) is a hybrid plant derived (in France) from species brought originally from South Africa. Introduced to gardens in 1880 and first recorded in the wild in 1911 and is now widespread over most of the UK. Montbretia is established in the wild from garden throw-outs and spreading naturally.

It is mildly invasive in the west of England, especially on coastal slopes and on hedgebanks in Cornwall, where it is thought to push out native plants. It was once sold at the sides of roads in Cornwall, marketed as ‘Cornish Heather’.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Carpet Sea Squirt

The Carpet sea squirt (Didemnum vexillum) is a marine hitchhiker from the North West Pacific and was first recorded in the UK in 2008. This brownish, tube-shaped, sea squirt lives in colonies and spreads fast once established on the seabed. As the colony grows, it smothers local marine life and becomes a serious threat to biodiversity.

While each individual organism is only 1mm in length its colonies can cover several square kilometres, and any species that gets in its way. It is a nuisance for anglers and boat owners as it clogs up fishing equipment, covers boat hulls, and smothers reefs.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

American Skunk Cabbage

The American skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) is another plant from North America, it was introduced in 1947 by ornamental plant collectors, who admired it striking flowers. It has huge leathery leaves, between 40cm – 1.5m in length and has bright yellow flowers up to 45cm. Seeds are dispersed via waterways but also by birds and animals.

It is now established in some wet woodlands across the UK, where it crowds out native plant species and makes its presence known by emitting a strong skunk-like odour. Given the popularity of this plant in gardens and its continued introduction into the wild, the problems are likely to increase. Although initial invasions will expand slowly, once this plant takes hold it can spread rapidly and become a serious problem.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Floating Pennywort

Floating pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides) is a North America aquatic plant that was first recorded in the UK in 1990, having spread from garden ponds and aquaria into the wild. It forms dense mats of rounded leaves that float across the water’s surface. It is most common in the wild, in south east England.

It can grow up to 20cm a day, quickly covering whole water bodies and harming aquatic wildlife by blocking out sunlight and reducing oxygen availability in the water. Also, it interferes with recreational activities like angling and makes it difficult for boats to move around.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

American Bullfrog

The American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) is native to America and has earned itself the reputation of being one of the most harmful invasive amphibian species, as it feeds all day and night on a wide range of prey, outcompeting native species for food. It also carries a disease called Chytridiomycosis, that has led to worldwide amphibian decline and several global extinctions.

These frogs are huge compared with our native frogs, as adults can grow to 25cm in length.

In the past, American bullfrogs have been kept as pets and released into the wild as adults, spawn or tadpoles in nearby ponds. In 1999 they bred for the first time at a site in England but have since been controlled.

Please do not release any unwanted pets into the wild as it could harm native wildlife!

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Asian hornet

The Asian hornet (Vespa velutina) poses a significant threat to the UK’s wildlife as it is a significant predator of Bees. They are relatively new to Britain, the first sighting was in 2016 in the town of Tetbury, in Gloucestershire. Since then, there has been 17 confirmed sighting in total in the UK including Cornwall.

The Animal and Plant Health Agency quickly locates and destroy any Asian hornet nests, but it is possible that this species could reappear so please keep an eye out!

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Japanese Knotweed

Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) as the name suggests, is native to Japan and was introduced to the UK by the Victorians as an ornamental plant. It is a rhizomatous herbaceous perennial, meaning it spreads by its underground roots and the vegetation dies back each year.

It can be identified by its zig-zig stems, that are shaped like shields, with a flat base. The stems are speckled with purple, have regular nodes and there is a rhizome crown at the base of the plant. These rhizomes can spread up to 8m from the shoot and are orange inside. It flowers in the UK in late August and September, then in the autumn, the leaves will start to go yellow and wilt as winter approaches. The stems will change to a darker brown before the plant becomes dormant in winter. It can grow to about 2 or 3 metres if left unattended.

Japanese knotweed presence has many negative impacts including, outcompeting native flora through shading and contaminating construction materials such as brickwork, tarmac and concrete, while it is very hard to eradicate due to the tendency of the rhizomes to spread out from the plant.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

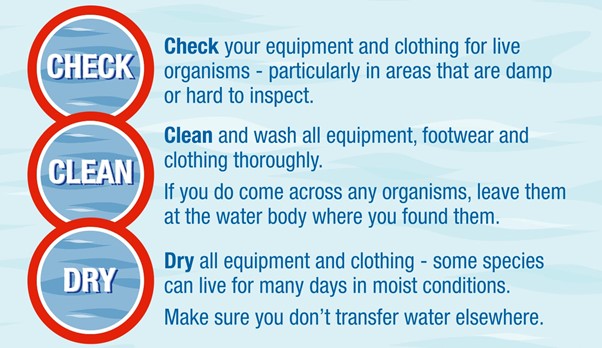

Check Clean Dry

Stop the spread of Invasive Non-Native Species by following these three steps!

People can provide a fast track for invasive species to spread from one location to another, sometimes intentionally but more often accidentally.

With Covid- 19 restrictions easing many of us may travel to different areas of the UK. Some of us are able to combine this with hobbies such as fishing, kayaking, swimming and boating. However, you could bring back more than just happy memories of your holiday.

You can easily avoid transferring invasive non-native species on your equipment by cleaning it before leaving a site, so all potential stowaways including plants and animals are left behind. The Check Clean Dry campaign offers advice on how to minimise this risk and damage that invasive species can cause on wildlife and the economy. Check it out at www.nonnativespecies.org/checkcleandry

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Himalayan Balsam

Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) was first introduced as a garden plant in 1839 but soon escaped. It can now be found along riverbanks and ditches across the UK, especially close to towns. As its name suggest it is native to the Himalayas.

It is the largest annual plant in the UK, growing up to 2.5m high from seed in a single season and can project its seeds up to 4m. Himalayan balsam has large pink-purple flowers, leaves with small red teeth at the edge and a stem that is reddish in colour.

Himalayan balsam can spread quickly and can form dense thickets, altering the ecological balance of wetland habitats. Due to being an annual plant, it only needs short roots, which can result in the erosion of riverbanks during the winter when the plant has died back. Many seeds are dropped into the water and contaminate land and riverbanks downstream. It also produces a lot of pollen, attracting many pollinating insects which is creating concerns that its presence may result in decreased pollination of native plants.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – CINNG

Native, Non-Native or Invasive?

Here at CINNG we talk a lot about native, non-native and invasive species but what is the difference?

Native Species – are species that have originated, evolved and developed in their surrounding habitat, having adapted to living in that particular ecosystem with other native species, through natural processes.

Non-native, alien or introduced species– are species found outside their native range, often moved through human activity. Not all of these species are invasive, many can thrive in new areas without posing a threat to the native ecosystem or the species within.

Invasive species – are species outside their native range that have negative impacts on other species and or the environment. Within their native range their population size could be controlled by predators, herbivores or parasites, while these control species may not be present in their new areas. This gives invasive species a chance to take over and dominate, often leaving native species in reduced numbers or being removed completely. Invasive species are often well suited to their new environment.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Giant Hogweed

Another of our invasive non-native species from Asia that is causing a lot of issues in the UK is giant hogweed (Haracleum mantegazzianum), as its sap can burn skin.

Giant hogweed originates from the Caucasus Mountains and Central Asia. It was first introduced to the UK as an ornamental plant in the 19th century, where it escaped and has now naturalised into the wild. It can now be found throughout much of the UK, especially colonising riverbanks where its seeds can be transported by water, helping it spread.

It contains furocoumarin, which makes skin extremely sensitive to sunlight, known as phytophotodermatitis. When the sap gets onto people’s skin and they are then exposed to the sun, their skin can blister. This blistering can recur over months and even years, this is known as phytotoxicity.

The best way to avoid injury is to learn how to identify the plant (see photo). When it’s fully grown it can reach towering heights of between 1.5 to 5metres and has a spread of between 1 to 2metres. It forms a rosette of jagged, lobed leaves in the first year, before sending up a flower spike in the second year and setting seed. Flowers appear in June and July; they are small, white and/or sometimes slightly pink. The flowers cluster on umbrella-like heads known as umbels that can reach a diameter of 60cm. All the flowers on the umbel face upwards.

It is also important to avoid brushing through patches of giant hogweed and exposing yourself to plants which have been cut and could get sap on your skin. If you do get sap on your skin, be sure to wash the areas thoroughly immediately, seek medical advice, and do not expose the area to sunlight for a few days.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – NNSS

Chinese Mitten Crab

This week on around the world with CINNG, we are moving away from Europe and into Asia with the Chinese mitten crab (Erichier sinensis). This is an instantly recognisable species due to the hairs on its claws and the fact it spends time in both freshwater and saltwater environments. This species is native to Asia but has now become an invasive non-native species in the UK.

The Chinese mitten crab is medium-sized with long, spindly, hairy, legs and white-tipped claws, see photo. They are usually dark green in colour, although some may be brown or even orange. It is unclear why they develop hairs as they do not appear to serve any purpose.

Chinese mitten crab was first recorded in Europe in 1912 (1935 in the UK), and in the Great Lakes in the US and Canada in the 1960s. It is not clear how this species established a presence so far away from their natural range in Asia. Although the most like explanation is the larva of this species had been transported in the ballast water of commercial ships.

These crabs can be very damaging to environments, outcompeting native crustaceans for food and stripping the bait in pots, removing commercially valuable species. They burrow into riverbanks causing them to collapse and even causing dams to become unstable. Huge downstream migration of Chinese mitten crabs has even caused water intake and turbines in dams to become blocked.

Attempts to remove or even control Chinese mitten crab numbers in areas where they have established themselves have proven to be very difficult. This is because the species is physically hardy, able to survive in high polluted waters and can move and function when it has taken on damage which would have killed or disabled other species. Its high mobility and migratory patterns also make it difficult to trace where they are present.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – FEPA

Zebra Mussel Project

For the final mussel post, CINNG is delighted to tell you about our Zebra mussel project based in Bude Canal, Cornwall. We would like to say a massive thank you to South West Water for funding the project. This photo was taken during a Zebra mussel survey before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) have financial and ecological impacts on a wide range of stakeholders, including water companies, boat yards and marinas. It currently has the highest control cost of any invasive non-native species in the UK due to the need to manage infestations at water supply and treatment works. These costs are associated with the removing of bio foul, repairing damage to water tanks/pumps and clearing blocked pipes. Juveniles in particular are known to attach themselves to the hulls of boats, which allows them to dispersal to new areas, both overland and by water.

Bude is a small seaside town in Cornwall, with a thriving tourism industry and a canal that is used for recreational purposes, including angling, boating and other water sports. The presence of Zebra mussels is causing concern, particularly as recreational users of the canal may also use other facilities, both locally and nationally, and could, unintentionally spread the mussels to new locations.

This site is currently the only known location in Cornwall where Zebra mussels are present, so provides a good location to study their effects and movements. The aims of our project are to raise awareness of the negative impact that Zebra mussels have on freshwater ecosystems and gather ideas from experts on possible controls.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – CINNG

Zebra Mussel

Continuing with the mussel theme, here is the Zebra mussel (Dressena polymorpha). This species has the highest control cost of any known invasive non-native species UK as it can block water pipes and smother boats.

Zebra mussels are a freshwater species native to southern Russia and Ukraine and is found in a wide range of habitats including both freshwater, brackish rivers, estuaries and lakes. First recorded in the UK in 1824 it has now been documented in over 3,000 sites, one of which is Bude Canal, Cornwall.

This species, like the Quagga mussel is a highly efficient filter feeder and lives in large numbers in its invaded ranges. A population of zebra mussels has a feeding rate of up to 10 times that of our native mussels. This negatively effects the freshwater ecosystems by outcompeting our native species for food. They also colonise on our native freshwater mussel (unionidae) which prevents them from feeding.

Once established in rivers or reservoirs there is currently no effective eradication method, but you can help to stop the spread by thoroughly cleaning any equipment used in the water and following the ‘check, clean, dry’ campaign.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Quagga Mussel

The first mussel species we are going to tell you about this week is the Quagga mussel (Dreissena bugensis). This is a freshwater mussel, native to the Ukrainian section of the Black Sea. Since the 1940s it has spread across western Europe and was first recorded in the UK in 2014, within the River Thames.

The Quagga mussel is a prolific breeder; a fully mature female mussel can produce up to 1 million eggs in a year. This and their ability to filter out large quantities of nutrients from the water have negatively affected the freshwater ecosystems and reduced native species. They are also known to block water pipes and smother boats.

Once established in rivers or reservoirs there is currently no effective eradication method, but you can help to stop the spread by thoroughly cleaning any equipment used in the water and following the ‘check, clean, dry’ campaign.

Invasive species such as Quagga mussel can cost the UK economy in excess of 1.8 billion every year.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – Geological survey

Killer Shrimp

Today it is the Killer shrimp’s (Dikerogammarus villosus) turn in the spotlight. It is considered one of the most damaging non-native species in the UK. It has been linked to play a part in the decline of native freshwater shrimps as well as some mayfly, stonefly and caddisfly species.

The Killer shrimp are native to the Black Sea region, but over the past 20 years have spread across western Europe, most likely through commercial shipping. It was first discovered in the UK in 2010.

Killer shrimp are able to survive in a variety of environments, but prefer to colonise in slow to moderate flowing water. They live for roughly one year with the females being able to produce three broods in their life time, each with an average of 100 to 150 eggs.

They are omnivorous, meaning that they feed on a variety of food including that of both plant and animal origin. They are known to prey on other invertebrates (insects, crustaceans, molluscs and worms), fish eggs, as well as small fish.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – Environment Agency

European Rabbit

Who doesn’t like spotting rabbits hopping around the countryside? However, they cost the economy more than £260m a year through damage to crops, businesses and infrastructure.

The European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is native to southwestern Europe (including Portugal, Spain and western France) and to northwest Africa (including Morocco and Algeria). It has been widely introduced around the world to all continents except Antarctica and to many oceanic islands, often with devastating effects on local biodiversity.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

American Mink

This American mink (Neovison vison) is looking forward to its Christmas dinner! Unfortunately, many mink will be having dinner away from its native home of North America, as they are now an invasive non-native species in the UK. Mink were brought over for trade and fur farms in 1929. However, since then many escaped or were deliberately released into the wild. The first record of them successfully breeding in UK was in 1956, now they are widespread over the UK, apart from in the far north of Scotland.

American minks are small semi-aquatic mammals, they occupy both freshwater and marine habitats and follow waterways, lake edges and coasts. They have rich, usually dark brown fur and a small white patch on the chin or throat. Mink are carnivores eating a wide range of prey including, rabbits, water voles, rats, birds, eggs and fish. They are opportunistic hunter feeding on whatever’s available at the time.

Minks are such an effective hunter they are now having a negative impact on native wildlife populations. They are known to be one of the biggest causes in the 94% decline in water vole populations and are also thought to be responsible for the disappearance of the moorhen from Hebridean islands of Lewis and Harris. As well as this they are impacting on economic activities such as fish farming, crofting, sports angling, and tourism.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species.

Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Photo copyright – GBNNSS

Check out our ID guide for more information.

Alpine Newts

Have you seen this invasive newt?

The market for exotic pets is growing, creating a greater implication for conservation and native biodiversity. It is important to think twice before buying pets as presents for Christmas.

The Alpine newt (Ichthyosuara alpestris) is native to central Europe but has now become an invasive non-native species in the UK. They were introduced into the UK in the 1920s as pets for garden ponds, due to their good looks.

Since being introduced, some Alpine newts have escaped into the wild, where they can have negative impacts, depending on the location and other species present. They can carry an infection called Chytridiomycosis, which attacks native newts’ skeleton and skin. The Chytrid fungus is waterborne, so can easily be spread between waterbodies. Therefore, it is important to clean and disinfect any footwear/equipment before moving between waterbodies, to avoid the spread of this infection.

Adult Alpine newts can grow to between 7-12cm and are usually brown, green, blue or grey, sometimes with a marbled pattern on the back and sides. They have a bright orange unspotted belly and throat. Males have a low, smooth, yellowish crest, with black spots or bars during the breeding season.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that invasive non-native species (INNS) are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help protect and preserve our native species. Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord.

Grey Squirrels

Happy Thanksgiving to all the Grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) living in their native range of North America. They are common in the UK too but here these little mammals are an invasive non-native species (INNS).

Since being introduced to the UK in the 1890s these attractive little animals have caused a great deal of environmental damage. This includes decimating the UK’s native red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) population by outcompeting them for food and resources. Also, greys can carry a virus called squirrel pox which they have immunity to, but when transmitted to red squirrels, often leads to their death. This means that the reds are now only found in places where grey squirrel populations are low or absent, such as in the pine forests of Northumberland and the Lake District. Grey squirrels are also affecting the composition of UK native woodland by stripping bark and eating seeds.

It is important to raise awareness about the negative impacts that INNS are having in the UK. If you have any photos of INNS, please share with us as increased awareness can help maintain native species. Please record your sightings in Cornwall through the CINNG Submit a Sighting page. Or for national records, use iRecord. Happy Thanksgiving!

Check out our ID guide for more information.

https://cinng.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Grey-Squirrel-Final.pds